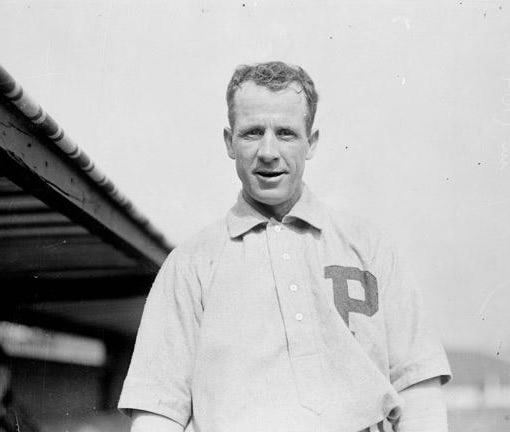

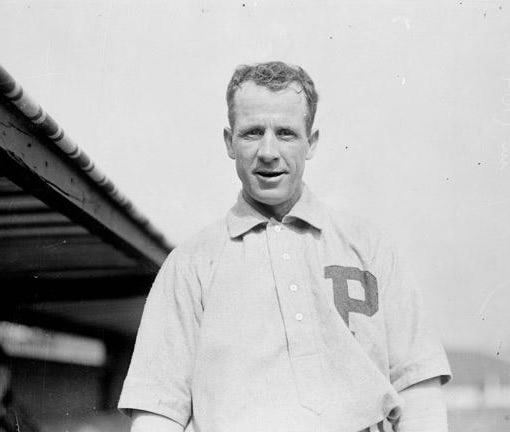

Kid Gleason, inaugural member of the Hall of Clearly Above Replacement by Not Quite Average

(image via Wikimedia Commons)

You have probably heard about the new Hall of Nearly Great eBook. It is a project curated by Sky Kalkman and Marc Normandin that celebrates some of the forgotten greats of the game. The fact that a player is not a Hall of Famer doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be remembered.

One morning, I was looking at the ebook’s table of contents along with my wWAR spreadsheets. I found that (of course) there are enough great players outside of the Hall of Fame to fill several volumes of Hall of Nearly Great books. As comprehensive as the Sky and Marc’s book was, there were still players like Dave Stieb, Wes Ferrell, Ken Boyer, Ron Guidry, Vida Blue, Deacon White, Doc Gooden, and so, so many others. I posted some of these names on Twitter.

My friend Dan McCloskey tweeted back:

“Once they work down to the Hall of Clearly Above Replacement But Not Quite Average, I want to contribute.”

I doubt Sky and Marc will reach down that far, so that’s what Dan and I are organizing today. Consider this an homage to the Hall of Nearly Great. Just like the book, we’re going to cover 43 players. Just like the book, we’ve invited some guest authors. Unlike the book, we don’t have an author for each player. Also, we’re capping the player bios at 100 words. This is a blog post, not a book!

Today, we give you The Hall of Clearly Above Replacement, But Not Quite Average.

Criteria

For a player to be considered for this honor, he must have a career Baseball-Reference Wins Above Replacement (WAR) above 8.0—but have a Wins Above Average (WAA) total less than zero. In other words, he needs to be above replacement, but below average. In yet another set of other words, he needs to be below average, but still useful.

What’s the Difference Between WAR and WAA?

All components of WAR are expressed in runs above or below average, not replacement. These numbers are then added up and a replacement adjustment is made. WAA is basically WAR without this replacement adjustment. Last week, my first High Heat Stats article covered the difference between WAR and WAA in detail.

The Authors

We have six talented authors. I also contributed, giving us a total of seven.

- Andy (@HighHeatStats) is… well, if you’re reading this blog, you should already know what he is.

- Dan McCloskey (@_LeftField) is a husband, a new father, a Systems Librarian by day, a music-obsessed baseball fanatic—who’s been to 24 Hall of Fame induction ceremonies—and craft beer enthusiast in his (very limited) free time. Most of his work can be found at his personal blog, Left Field.

- Stacey Gotsulias (@StaceyGotsulias) writes words about baseball for Aerys Sports and The Yankee Analysts. When she’s not hanging out at home with her five cats (No, that’s not a typo), she can be found in the last row of the Yankee Stadium upper deck cheering on the boys from the Bronx.

- Born and raised in southern New England, Bill Miller (@Raindog63), a life-long Mets fan, now lives and blogs in Greenville, S.C., where to criticize Shoeless Joe Jackson is akin to casting aspersions upon Jesus, College Football, and the old Confederacy, not necessarily in that order.

- Graham Womack (@grahamdude) is the founder and editor of Baseball: Past and Present as well as a contributor to this website.

- Bryan O’Connor writes about MVP races, Hall of Fame cases, and how to evaluate aces at Replacement Level Baseball Blog. A nonprofit accountant, advocate for equal rights, and Fangraphs devotee, Bryan lives with his wifeand two young children in South Portland, Maine.

- Adam Darowski (@baseballtwit) is a husband, dad of three, a web developer, and a baseball researcher focused on the Hall of Fame. Much of his research can be found at the Hall of wWAR. He writes for Beyond the Box Score, Baseball: Past and Present, and this site.

Next, Your Turn

We covered 43 players, but there 441 who fit our criteria. You can find the rest in this Google Spreadsheet. If you see someone you like, please take part. Pick a player and write 100 words about him. These were useful players who deserve to be remembered.

The Players

Here they are, sorted by WAR.

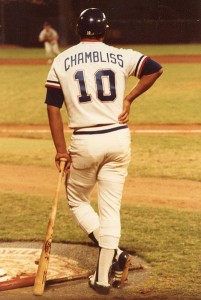

Kid Gleason (1888-1908, 1912; 35.5 WAR; –3.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Kid Gleason, most famous for managing the 1919 White Sox, was by far the most successful player in this Hall. He collected nearly 2,000 hits as a second baseman and also earned 138 victories on the mound, peaking with 38 wins in 1890. He was a much more valuable pitcher (29.4 WAR/11.7 WAA) than a hitter (6.1 WAR/–15.1 WAA), but when you merge his numbers, they fit the criteria. No player in history has hit as often and pitched as often as Gleason (though John Montgomery Ward comes very close on both counts).

Joe Niekro (1967-1988; 26.2 WAR; –1.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

I suspect people think Joe and Phil Niekro were closer in value than they really were. The truth is, the knuckleballing brothers had a WAA disparity nearly as large as Cal and Billy Ripken (57.8 difference to 53.2). Joe accumulated 26.2 WAR by hanging around for a long time. His 500 starts rank 45th all time while his innings total ranks 63rd (he’s even 101st in strikeouts). He was at his best with Houston, the team for which he still owns the win record. Niekro won twenty games twice, but peaked in 1982 (with 17 wins and 6.5 WAR at age 37).

Lew Burdette (1950-1967; 24.8 WAR; –1.0 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

I was surprised to see that Lew Burdette (who received 24% of the Hall of Fame vote in 1984) was a slightly below average pitcher. The 1957 World Series MVP won 203 games with a sparkling .585 winning percentage, but his 3.66 ERA translates to just a 99 ERA+. While his ten-year peak produced 163 wins (fourth from 1952 to 1961) against only 106 losses, it only produced 23.9 WAR (placing 14th) and 3.6 WAA (his non-peak years brought those numbers down further). One might suggest that many of those wins belong more to Henry Aaron and Eddie Mathews than Burdette.

Don Baylor (1970-1988; 24.4 WAR; –2.4 WAA)

by Graham Womack

It seems counter-intuitive to think of a player with 330 home runs, a 118 OPS+ and 24.4 WAR as a below average player. Maybe that’s the essence of this project. Look a little deeper with Don Baylor and there are plenty of things to justify the –2.4 Wins Above Average that he compiled over the course of his career. There’s his –22.9 defensive WAR, his rating for the stat negative 16 of his 19 seasons. And for supposedly making his mark at the plate, Baylor batted .260 lifetime, hitting above .300 and posting a slugging line above .500 just one time apiece for each stat.

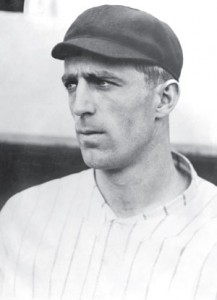

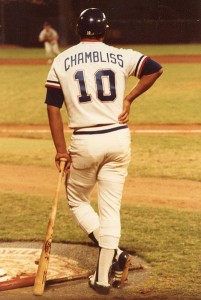

Chris Chambliss, the owner of 23.4 WAR, still comes in slightly below average.(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Chris Chambliss (1971-1986, 1988; 23.4 WAR; –1.4 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Having grown up a Yankees fan who counts Chris Chambliss’s walk-off home run to clinch the 1976 ALCS among my first baseball memories, it’s hard to think of him as below average. In fact, his 23.4 WAR ranks among the highest of players who satisfy the criteria for this project, as he was better than replacement for 15 of his 17 major league seasons. Chambliss enjoyed his best regular season in 1976 as well, hitting 17 homers and driving in 96 runs to go with a 124 OPS+ and 3.8 WAR, and tying Rod Carew for 5th in MVP voting.

Joe Kuhel (1930-1947; 21.8 WAR; –2.9 WAA)

by Graham Womack

Joe Kuhel was an American League first baseman from 1930 to 1947, a Golden Age for that position in that circuit. When people talk of standout AL first basemen from those days, I suspect they talk of Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg and Jimmie Foxx and, to a lesser extent, Hal Trosky, Zeke Bonura and Rudy York. I’ve never heard anyone pay tribute to Joe Kuhel, and there’s good reason for this. There’s nothing memorable about a player who averaged seven home runs a year in the 1930s and later had a .257/.352/.349 slash line playing through World War II because he was past draft age. It makes sense Kuhel finished with –2.9 Wins Above Average.

Joe Vosmik (1930-1941, 1944; 18.6 WAR; –0.5 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Joe Vosmik, the son of Bohemian immigrants, was born in Cleveland and starred for the Indians (while later playing for Browns, Red Sox, Dodgers, and Senators). He played during the offensive explosion of the 1930s, posting his best season in 1935 (when he led the league in hits, doubles, and triples while hitting .348 with 5.6 WAR). He hit .300 five other times and owned a career average of .307. Due to the era, that only translates to an OPS+ of 104. He fanned just 272 times in 6088 career PAs, whiffing only 10 times while hitting .341 in 1934.

Orlando Cabrera (1997-2011; 18.1 WAR; –5.2 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

What I remember second-most about Orlando Cabrera (after whom I once named a goldfish) was the Gold Glove he won in 2001, when I still cared who won Gold Gloves. His Jekyll-and-Hyde UZR history half-belies his excellent defensive reputation, but the Gold Glove voters were surprisingly observant, rewarding him in two seasons in which UZR tells us he saved double-digit runs with his glove. What I remember most is his effect on the 2004 Red Sox, from the home run he hit in his first at-bat with the team to his ten-game postseason hitting streak to the personalized handshakes he invented for every one of his teammates. My all-time favorite player played 58 regular season games for my favorite team.

Jim Clancy (1977-1991; 17.9 WAR; –1.2 WAA)

by Andy

Jim Clancy is widely remembered as the pitcher with the most losses in the 1980s. The reality is that he was a very reliable starter for an average team. Between 1980 and 1987 Clancy was one of just 10 pitchers with at least 5 seasons of 120 IP and an ERA+ of 109. Fantastic he wasn’t, but dependable he was. He posted 4 different seasons with at least 3 WAR and only a couple worse than –1 WAR. In just this time with Toronto, Clancy accumulated 22.6 WAR and 5.5 WAA—a nice career. It was his few bad years in Houston and Atlanta that dragged down his totals.

Fred Merkle (1907-1920, 1925-1926; 17.6 WAR; –0.6 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

Even more than Bill Clinton or the sitcom Growing Pains, Fred Merkle is best known for a costly boner. Merkle likely cost his Giants the pennant in 1908 by not touching second base on what looked like a game-winning single by teammate Al Bridwell. Lost in this unfortunate legacy is a solid career, featuring an OPS ten percent better than league average over sixteen seasons, five of which ended with trips to the World Series. Sadly, like the 1908 season Merkle would have loved to erase, those World Series trips all ended with Merkle’s team—whether the Giants, Dodgers, or Cubs—losing its final game.

Jack Tobin (1914-1916, 1918-1927; 17.4 WAR; –1.7 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Jack Tobin was one of the stars of the Federal League in 1915, the final season of its two-year existence, and was the second most valuable position player (by WAR) for the league champion St. Louis Terriers. His 184 hits led the league, and he also ranked tied for fourth in runs, third in total bases, and in the top ten in doubles, triples, home runs, walks and stolen bases. After the league folded, he moved across town to play with the AL’s St. Louis Browns for nine seasons, playing third-fiddle in outfields alongside Ken Williams and Baby Doll Jacobson.

George Bell (1981, 1983-1993; 17.0 WAR; –1.6 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

When I saw George Bell’s name on the eligible list, two thoughts came immediately. The first was that Bell’s 1986 Topps baseball card called him Jorge, while the previous and subsequent years’ cards displayed his anglicized name. The second thought was outrage at one of the heroes of my youth—the 1987 AL MVP!—might be considered below average. Further investigation revealed that the years had exaggerated the numbers on the back of Senor Bell’s tarjeta de beisbol. He slugged .605 in ’87, but reached .500 only once more in his relatively short career. He struck out more than twice as much as he walked and led all left fielders in errors three straight years in his prime. Another hero deflated.

Pete O’Brien (1982-1993; 16.5 WAR; –1.1 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Talk about playing in the wrong position at the wrong time. Poor Pete O’Brien was a pretty good first baseman but he played at the same time as guys like Don Mattingly, Eddie Murray and Wally Joyner. Because of this cruel twist of fate, O’Brien never made an All-Star team. His career lasted from 1982-1993 and one time, in 1986, he was 17th in MVP voting. He finished his career .261/.336/.409/.725.

Ray Sadecki (1960-1977; 16.4 WAR; –3.7 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Ray Sadecki’s first season in the Majors in 1960 saw him finish 9-9 with a 3.78 ERA. After 18 years Sadecki finished his career with a 135-131 record and 3.78 ERA. In between, he was up, down and all around, played with six teams and helped the St. Louis Cardinals to a World Series title in 1964. To be fair, Sadecki helped the 1964 St Louis Cardinals to a World Series much in the way that Kenny Rogers helped the 1996 New York Yankees to a World Series title, he’d give up a bunch of runs and have to be relieved early.

Jeff Conine (1990, 1992-2007; 16.0 WAR; –5.9 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Did you know that Jeff Conine was originally a pitcher? He was taught how to play in the outfield before his Rookie of the Year campaign in 1993 with the Florida Marlins. The two-time World Series champion was a solid player during his 17-year career finishing with a line of .285/.347/.443/.789 and 214 home runs. His best years were early and while he was with the Marlins. He ended up playing with six teams before retiring in 2007.

Felix Millan (1966-1977; 15.9 WAR; –2.7 WAA)

by Bill Miller

Second baseman Felix Millan played for the Braves and Mets from 1966-77. His lack of power (22 career homers) and sluggish career OBP (.322) was partially offset by his ability to make contact. He was the toughest N.L. batter to strikeout four times in the 1970’s. Millan held the Mets record for hits in a season (191 in 1975) until Lance Johnson broke the record in 1996. His career WAR (16.9) is primarily a testament to his solid defense. Millan’s career ended prematurely in ’77 when Pirates catcher Ed Ott used Millan as a pile-driver during a scuffle at second base.

Mike Caldwell (1971-1984; 15.9 WAR; –2.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Mike Caldwell was a classic Yankee killer, going 13-8 with a 3.05 ERA and five of his 23 career shutouts against the Bronx Bombers. He finished second to Ron Guidry in AL Cy Young voting in 1978, and was responsible for handing Guidry one of just three losses that year. A late bloomer who wouldn’t have made this list if not for a sub-par early career, he also ranks second on the all-time Milwaukee Brewers list in wins (102) and was 2-0 with a 2.04 ERA in their 1982 World Series loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Joe Carter (1983-1998; 15.6 WAR; –10.8 WAA)

by Andy

Joe Carter is not a star—he’s the very definition of an average player. In 1990, Carter put up 115 RBI and got noticed nationally. The neat trick is that he drove in all those runs with just an 85 OPS+, the lowest OPS+ all-time for a player with at least 111 RBI in a season. Carter, in 1997, also had the lowest OPS+ (77) all-time of any player with at least 102 RBI in a season. Over his career, he was given a ton of RBI opportunities. In 1990, for example, 26.9% of all NL plate appearances came with runners in scoring position. For Carter that year, the figure was 33.1%. He did decently with what he was given, and that’s what he was as a player–decent.

I know this is Dave Kingman, but I have no idea what the hell he’s doing here. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Dave Kingman (1971-1986; 14.7 WAR; –6.7 WAA)

by Bill Miller

Whatever block of wood Dave Kingman was carved out of was tall, narrow, and devoid of mirth. His 442 career homers threw a scare into many that, if he stuck around long enough to hit 500, it would present difficulties come HOF voting time, for Kingman was a terrible player. Luckily, the Kingman show (strikeout / home run) was cancelled after 16 seasons with seven teams. Led his league in home runs twice, strikeouts three times and pleasant interviews never. Came up as a pitcher, but impersonated a position player for several years before his glove was taken away and buried.

Del Unser (1968-1982; 14.4 WAR; –2.7 WAA)

by Bill Miller

In his best season, Del Unser batted leadoff (someone had to) and played centerfield for the ’75 Mets. With a little hitch in his swing, Unser hit line-drives (with a smidgen of power) for five teams in 15 years. Unser was prone to the acrobatic catch in centerfield, perhaps mimicking PHEENOM Freddy Lynn of Boston. Later in his career, after a trade to Philadelphia, Unser sported a porn-star mustache. The direct impact of said mustache upon his baseball career is ambiguous, but this .258 career hitter (who once led the league in triples) was essentially done in the Majors by age 35.

Jody Reed (1987-1997; 14.0 WAR; –1.1 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

If you Googled Jody Reed today, you’d think the only thing he ever did was make a huge contract gaffe. After the 1993 season, he chose not to accept a three-year deal with the Dodgers worth $7.8 million. He would eventually sign with Milwaukee for the minimum. I remember Reed as something of an early day Dustin Pedroia. The numbers don’t come close to backing that up, but he was worth 12.9 WAR from 1988 to 1991 for the Red Sox. He led the AL with 45 doubles in 1990 and topped 40 two other times.

Lee Mazzilli (1976-1989; 13.9 WAR; –0.4 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Lee Mazzilli was supposed to be a superstar, but things didn’t quite work out that way. While he did flash his star potential early on with the Mets (peaking at 4.7 WAR in 1979), for most of his career he was just a solid bench player. That’s exactly what he was when he returned to his hometown team (after being traded to Texas for Ron Darling, followed by stints with the Yankees and Pirates) in 1986. As a key pinch-hitter, Mazz contributed hits to game-tying rallies in both games six and seven of the Mets’ 1986 World Series victory.

Brad Ausmus (1993-2010; 13.6 WAR; –5.8 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

There aren’t many people who caught as much—and as well—as Brad Ausmus. The Ivy League (Dartmouth) backstop ranks 7th in games caught, 9th in Total Zone runs (99), and even 11th in our old friend Fielding Percentage (.994). While could catch, he certainly couldn’t hit much—his .251/.325/.344 slash line during the height of the offensive explosion gives him an OPS+ of just 75 (and –215 WAR batting runs). No Jewish player has appeared in more big league games than Ausmus, who will manage Team Israel at the 2013 World Baseball Classic.

Everett Scott (1914-1926; 12.6 WAR; –8.3 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

When Lou Gehrig played in his 1,308th consecutive game, he broke the record held by Everett Scott. Within the first five seasons of his career, Scott had already won three world championships as the light-hitting (65 OPS+)/slick fielding (+95 WAR fielding runs) shortstop and captain of the Boston Red Sox. After the 1921 season, Scott was traded to the Yankees and became captain of the Bronx Bombers, as well. He won another championship in New York (in 1923). Lou Gehrig began his consecutive games streak two days after Scott’s final game as a Yankee.

Tito Francona (1956-1970; 11.9 WAR; –4.4 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

Among baseball players who contributed more to the game through their progeny than through their own accolades, Tito Francona may not be Bobby Bonds or Ken Griffey, but he did sire perhaps the best manager in Red Sox history and one of its best budding color commentators. To ignore the elder Francona’s own ledger, though, is to miss a player who hit more home runs (125) than Ty Cobb and had the same career on-base percentage (.343) as Lou Brock. Accumulated in parts of 15 seasons, Tito’s 11.9 WAR (per Fangraphs) were 15.5 more than his son earned.

Rob Deer (1984-1993, 1996; 11.8 WAR; –1.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Oh my, Rob Deer was glorious. In 4,513 times at bat, Deer launched 230 home runs, walked 575 times, and fanned 1,409 times. Those three true outcomes and accounted for 49% of Deer’s plate appearances. One of the most amazing stat lines I’ve seen is Deer’s 25-game comeback with the Padres in 1996—64 PAs, 9 hits, 4 homers, 14 walks, 30 strikeouts, a .180/.359/.839 slash line, and an OPS of 125. In 1991, Deer had another ridiculous season, hitting .179 while qualifying for the batting title (a record low). He homered 25 times, walked 89 times, and whiffed 175 times. Rob Flipping Deer.

Bobby Witt (1986-2001; 11.8 WAR; –8.1 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Before there was Armando Galarraga, there was Bobby Witt. On June 23, 1994, Witt came painfully close to perfection. Greg Gagne was ruled safe on a sixth inning bunt although replays showed he was safe. He was the only baserunner Witt allowed while fanning fourteen. From 1986 to 1988, Witt joined teammate Mitch Williams in walking 604 batters (while fanning 762 and throwing 59 wild pitches) in 750 innings. Any time you meet Gene Petralli, Don Slaught, or Mike Stanley (their catchers), go easy on them. They also caught Charlie Hough.

Despite 2715 hits, Bill Buckner was a below average hitter. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Bill Buckner (1969-1990; 11.8 WAR; –17.2 WAA)

by Graham Womack

Bill Buckner was a good contact hitter, an RBI machine and he probably took undue grief from beleaguered Red Sox fans for muffing that ground ball in the 1986 World Series. After all, Buckner alone didn’t lose the championship. Regardless, the error pits Buckner with fellow goats like Fred Snodgrass and Fred Merkle and in comparison, Buckner suffers. Where Snodgrass compiled 4.4 Wins Above Average during his career and Merkle was at –0.6 WAA, Buckner amassed a ghastly -17.2 WAA. That’s the lowest of any man in this project, Buckner’s meager power, OBP and defense relegating him to a spot in sabermetric history worse than anything Game 6 could’ve provided.

Matt Stairs (1992-1993, 1995-2011; 11.7 WAR; –6.3 WAA)

by Andy

Matt Stairs topped 500 plate appearances in only 3 of his 19 seasons in the big leagues. A very poor defender, his –17.3 dWAR nearly negated all of his 20.4 oWAR, earned because the man carried a giant stick. Stairs holds the MLB record with 23 pinch-hit homers, which came in 490 plate appearances, and usually against ace relievers. He’s tied with Wally Schang for highest career OPS+ (117) among non-pitchers with at least 13 MLB seasons of 410 plate appearances or fewer. Stairs kept it up in the post-season, with a memorable pinch-homer in Game 4 of the 2008 NLCS, helping the Phillies beat the Dodgers.

Jack Graney (1908, 1910-1922; 11.6 WAR; –7.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Jack Graney’s career was full of firsts. He was the first batter to face Babe Ruth. He was the first official player to wear a uniform number. But, he is remembered most for being the first major league player-turned-broadcaster. The Canadian leftfielder followed up his 14-year Major League career (featuring a 101 OPS+ in 5,581 PAs—all with the Indians) by broadcasting Cleveland Indians games on the radio from 1932 to 1953. From a sabermetric perspective, he is the player with the highest career WAR (11.7) who never had a single above-average seasons (according to WAA).

Dick Tidrow (1972-1984; 11.2 WAR; –2.0 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Back in the days when effective relievers pitched 100+ innings a year, Tidrow was briefly one of the best setup men in baseball, although he had to go through some growing pains as a starter first. After three up-and-down seasons in Cleveland and New York, the Yankees moved him to the bullpen, where he posted a 126 ERA+ and was worth 4.2 WAR the next three years. Another failed attempt to start and a trade to the Cubs later, Tidrow had his two best seasons back in the bullpen (219 IP, 147 ERA+, 5.3 WAR) before fading into negative-WAA oblivion.

John Milner (1971-1982; 11.1 WAR; –0.3 WAA)

by Bill Miller

John “The Hammer” Milner was a first baseman/leftfielder who player primarily for the Mets and the Pirates from 1971-82. Through his age 24-season, he’d already slugged 60 home runs. He always appeared to be one small step away from stardom, but his home parks (especially Shea Stadium) and the era in which he played tamped down his production. Milner drew more walks (504) than strikeouts (473) in his career. His career OPS+ (112) is the same as HOFers, Sam Rice, George Kell… and some guy named Cal Ripken, Jr.

Chick Fraser (1896-1909; 10.7 WAR; –14.0 WAA)

by Graham Womack

Chick Fraser’s 3.67 ERA looks conspicuously out of place for a man whose career spanned 1896 to 1909, part of what we now call the Deadball Era. His 92 ERA+ is tied for tenth-worst among pitchers with at least 1,000 innings logged in those years, and none of the men in front of Fraser came anywhere close to his 3,364 innings. In fact, Fraser has the worst ERA+ of any pitcher in baseball history with at least 3,000 innings. If we drop it to 2,000 innings, he’s ninth-worst. Whatever the case, Fraser’s –11.2 Wins Above Average doesn’t look like any kind of sabermetric slight. He was historically bad and has a deserved place in this project.

Vince Coleman (1985-1997; 10.5 WAR; –6.6 WAA)

by Andy

Vince Coleman turned the NL on its ear when he arrived in 1985. This young firecracker led the league in stolen bases in each of his first 6 years. Surely he created a lot of value and it’s a mistake that he’s on this list, right? Wrong. The guy was at best an average hitter and had very little power. Over that 6-year period of 1985-1990, while he led MLB in stolen bases, he also led in caught stealing, managed just an 85 OPS+, generated just 11.0 WAR, and was below average at –0.4 WAA. And that was his career peak. Once he left St. Louis, he put up near-zero WAR the rest of the way.

Lee Richmond (1879-1883, 1886; 10.3 WAR; –2.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

It’s probably the case with all of the players discussed here that their careers, while considered below average by modern metrics, actually include some exceptional moments. Lee Richmond might be the ultimate example, having thrown the first perfect game in Major League history on June 12, 1880. In fact, his perfect game occurred before the term had even been coined. He compiled almost his entire career pitching value in 1880, his rookie season, going 32-32 with a 2.15 ERA and 119 ERA+ in 590 2/3 innings for the Worcester Ruby Legs, and accumulating 7.6 WAR.

Tony Clark (1995-2009; 10.1 WAR; –4.7 WAA)

by Andy

Tony Clark was a stud with the Tigers in the late 1990s. He averaged 32 HR, 106 RBI, and 125 OPS+ in 1997-1999, his first 3 full seasons in the big leagues. Unfortunately, those also turned out to be his last 3 full seasons, thanks to a seemingly endless string of injuries.Over the final 10 years of his career, he averaged just 97 games with a 106 OPS+. As a below average defender, his WAR suffered badly over those 10 years, except for 2005, when, in his finest hour as a major-leaguer, he produced 30 HR, 87 RBI, and 3.2 WAR for the Diamondbacks in just 393 plate appearances.

Lenny Randle (1971-1982; 9.7 WAR; –3.4 WAA)

by Bill Miller

After a few uninspiring seasons out in Texas (really, can you blame him?), third baseman Lenny Randle became the toast of Shea Stadium in 1977. Randle came to the Mets with a reputation for being surly (a term white reporters reserve for black players), but won over Mets fans with his speed (33 steals), his ability to get on base (.383 on-base percentage) and solid, sometimes spectacular defense. Unfortunately for Randle and the Mets, his age-28 season was not to be replicated. Marooned with the Mariners, Randle retired from baseball in 1982 with a desultory .257 career batting average.

Paul Foytack (1953, 1955-1964; 9.0 WAR; –1.7 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

There’s only one man able to commiserate with the nightmarish night Chase Wright experienced at Fenway Park in April 2007. That man is Paul Foytack, who Wright matched for the dubious distinction of being the only pitcher in MLB history to give up homers to four consecutive batters. Interestingly enough, one of the batters who took Foytack yard was Tito Francona, the father of the manager whose team victimized Wright. While that was the second of three appearances in Wright’s major league career, Foytack would pitch at a slightly below average level for close to 1500 innings over 11 seasons.

Chet Laabs (1937-1947; 8.7 WAR; –0.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

I’m not a memorabilia collector, but one of my favorite items is a framed 1939 Chet Laabs card. Why would I frame the trading card of a mediocre outfielder who retired 20 years before I was born? It’s a longer story than I can possibly tell here, but let’s just say my father’s vast knowledge of that era enters into it. Laabs enjoyed his best years during WWII, including a 27 HR, 99 RBI campaign in 1942, and was a member of the St. Louis Browns’ only World Series entrant: the 1944 team that lost to the Cardinals in six.

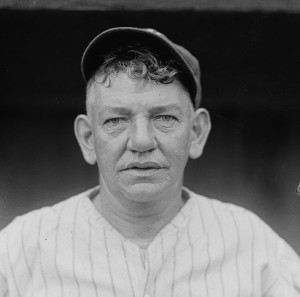

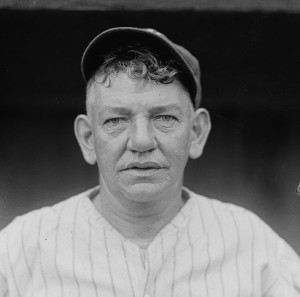

Nick Altrock may have played in five decades, but all of his career value came in four seasons (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Nick Altrock (1898, 1902-1909, 1912-1915, 1918-1919, 1924; 8.6 WAR; –3.5 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

A half century before Minnie Minoso recorded two plate appearances at age 54 in 1980, Nick Altrock was the first five-decade player in MLB history. Altrock’s road to that accomplishment was a little different from Minoso’s, though. A late-blooming but solid pitcher in his late 20s, Altrock’s ability flamed out early due to injury and possibly his lack of seriousness. The quality that allowed him to remain in the majors for so many years was his comic ability, as he entertained fans, distracted opposing players and occasionally took the mound or pinch hit into his 50s.

Pete Incaviglia (1986-1994, 1997-1998; 8.5 WAR; –4.9 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

There aren’t many home run records from 1985 that have not fallen. Pete Incaviglia, however, still holds the NCAA single season (48) and career (100) home run records established during his three years at Oklahoma State University. Baseball America named him the Collegiate Player of the Century. Inky was drafted by Montreal and immediately traded to Texas (leading to the Pete Incaviglia Rule), giving him a chance to skip the minors. Inky bashed 124 home runs in his five years with Texas—but also whiffed 788 times. His most valuable season came in 1993 with the NL Champion Philadelphia Phillies.

Carlos May (1968-1977; 8.1 WAR; –6.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

There were several reasons why Carlos May was best suited to be a DH, but when he lost his right thumb while on Marines reserve duty in 1969, it had to adversely affect his throwing ability. Unfortunately, the DH rule didn’t exist until a few years later, and realistically the injury likely affected his batting as well, but he was still a pretty good hitter and a pretty bad fielder for his career. May’s real claim to fame? He was born on May 17 and wore #17, making him the only player ever to wear his birthday on his uniform.

Glenallen Hill (1989-2001; 8.1 WAR; –3.3 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Glenallen Hill was built like a brick shithouse. I can say this because he bumped into me on a dance floor in New York City and sent me flying about three feet. It was the night the New York Yankees beat the New York Mets in the 2000 World Series, which earned Hill his only championship ring. He spent time with eight clubs during his 13-year career. He finished his serviceable career with .271/.321/.482/.804 and 8.1 WAR.

Thanks

Thanks to Dan McCloskey for his great idea (and letting me take it over). Thanks to Andy for welcoming me to the High Heat team, allowing me to post it here. Thanks to the wonderful writers to contributed. And thanks for reading!