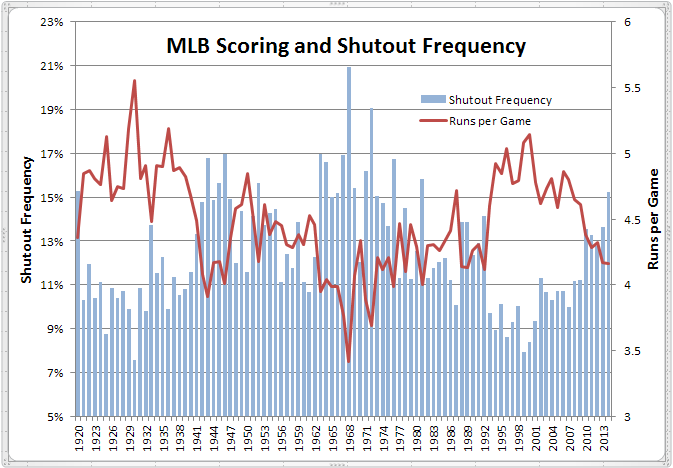

Thus far in 2014, the recent trend towards lower scoring continues. That trend is now more than 15 years in the making and has resulted in another, that of a higher incidence of shutouts (at least those of the team variety). So far in 2014, more than 15% of games have resulted in a goose egg for the losers, a proportion not seen since 1981, and not seen in a full-length season since 1976.

After the jump, more on declining offense and why it’s been happening.

To illustrate my point about shutouts and run scoring, here’s a chart of the live-ball era showing frequency of shutouts and average runs per team game.

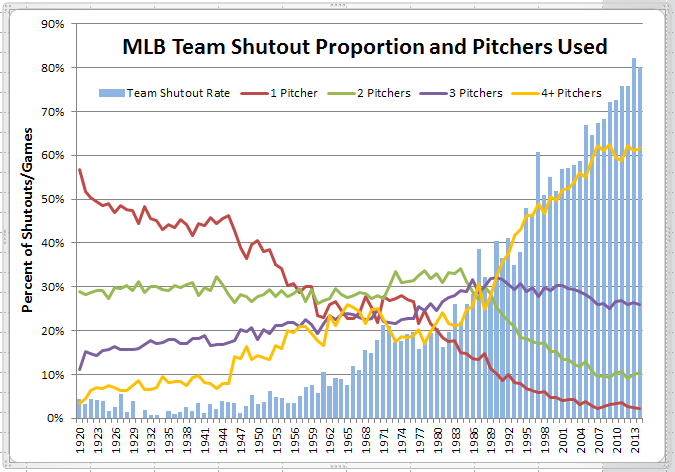

While both measures are now in the range experienced from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. how that has resulted in today’s game is markedly different from the past. That fact is illustrated in the chart below.

The blue bars represent “team shutouts” (those involving two or more pitchers) as a proportion of all shutouts. Almost negligible at the start of the live ball era, their incidence rose to about 20% by the early 1970s, doubling to 40% by the early 1990s, and doubling again to 80% today. That result is a byproduct of the other trends on the chart, showing the proportion of team games involving one, two, three and more pitchers, with reductions in the former two categories producing a huge increase in the latter category.

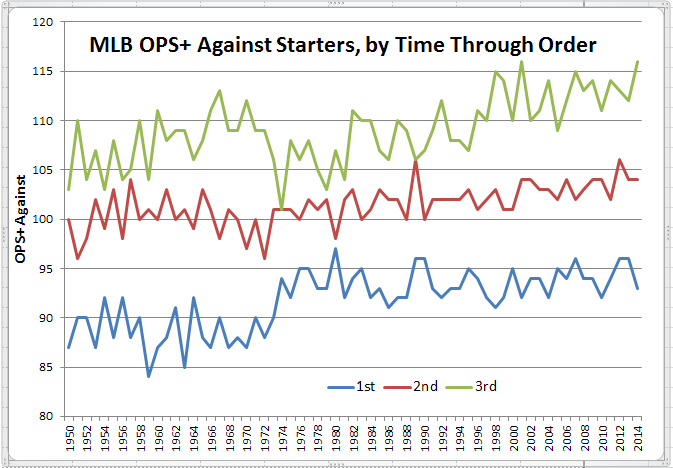

But, why has pitcher usage changed so dramatically? An explanation is indicated by the chart below, showing OPS+ against starting pitchers in the first, second and third times through the batting order.

These data are mostly complete for the period shown, since 1950. The effect of the DH is easily discerned, with an increase in OPS+ for the first and second times and a reduction (initially) for the third time, the latter an indication that the immediate response to the DH was for AL teams to go longer (but, only a bit longer) with their starters who, on the whole, did better than the relievers who had formerly been used in that spot. This effect was probably most pronounced in the circumstance of effective starters getting inadequate run support and thus having to be reluctantly removed for pinch-hitters. With the DH in effect, those starters remained in the game and continued to pitch effectively.

Also notable is the improvement in OPS+ over time, for each of the three times through the order. I’ll explain later why that has more to do with relief pitching than starting pitching. For now, the more important trend is that batters become more effective against starting pitchers each time through the order. So, should we expect that trend to continue for the fourth time through the order?

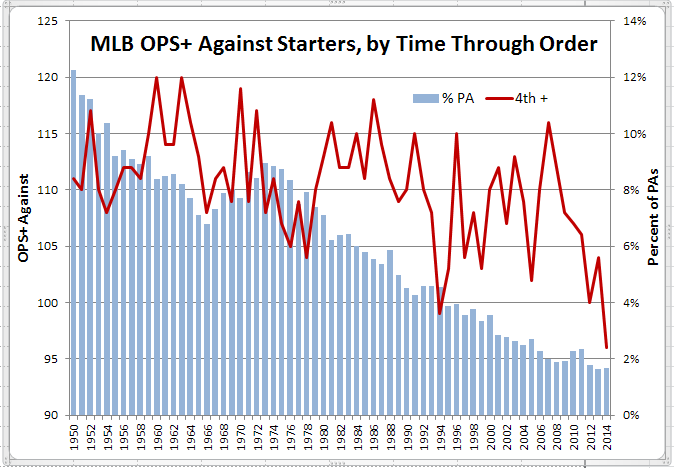

It did indeed through the early 1970s, with OPS+ scores (brown line) of 110 and higher, compared to a 105 to 110 range for the third time. But, those OPS+ scores then start to decline. But, only because of selection bias as indicated by the blue bars showing a corresponding decline in the proportion of PAs against starters in their fourth time through the order. Thus, only starters who were truly on their game were sticking around to have a fourth go at the opposition, while the rest were giving way to relievers. How did those relievers fare?

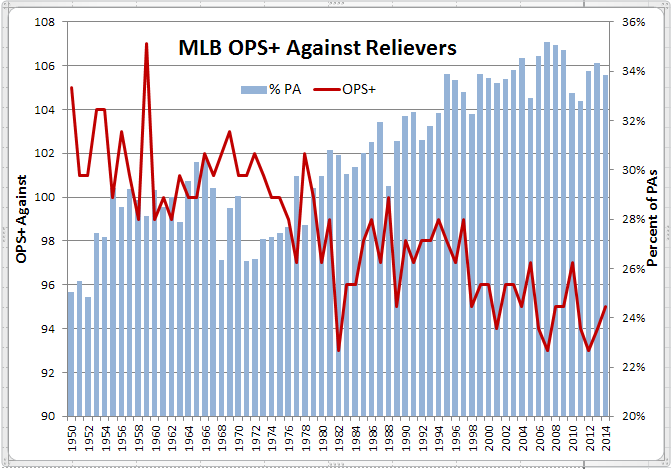

Prior to the DH rule, not so well with OPS+ scores inferior to those of starters. But since then, those OPS+ against scores have steadily improved, with a corresponding increase in the proportion of innings pitched. This result also explains the improved results (as measured by OPS+) for batters against starters. If relievers are doing better measured by OPS+ against, then starters must therefore be doing worse.

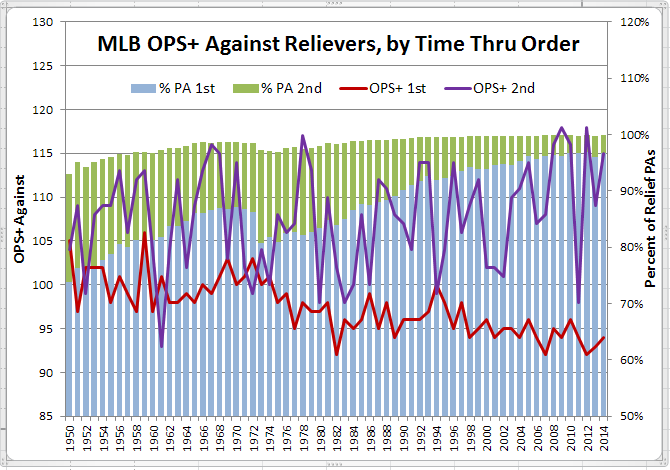

But, note that the proportion of PA by relievers has been basically level for the past 20 years, even as their effectiveness has continued to improve. The cause of that effect is suggested by the chart below, breaking down reliever usage and performance by times through the batting order.

Today it’s only in long relief that relievers stay in a game for a full tour of the batting order, much less more than one. But, it hasn’t always been thus. Even as late as the mid-1980s, 15% or more of relief PAs were against pitchers being seen for a second time. As with starters, relievers’ effectiveness was notably reduced their second time through the order.

But, note the last 15 seasons and the consistent 96 OPS+ or worse by hitters against relievers in their first (and, usually, only) look at them. Much as we might decry specialization of pitching roles and the resulting push-button managing of pitching staffs, bottom line is you can’t argue with success. Of course, it hasn’t all been the pitchers. Batters are doing their share by taking healthy cuts in *all* of their PAs, and thereby keeping an ever-increasing number of balls “out of play”. And, with ever-expanding pitching staffs come ever-shrinking benches, giving the defense the upper hand in late-inning matchups.

So, where are we headed from here? Let’s look again at my first chart.

As I noted earlier, runs per game and shutout frequency are both about where they were for a 20-year period from the early 1970s to early 1990s. Then came the offensive explosion of the 1990s and 2000s triggered, in part (perhaps a large part?), by PEDs. Now that PEDs appear to be mostly eliminated, is it just a coincidence that we’re back in the range of the relative offensive/defensive “equilibrium” of the pre-PEDs era? If not, is it reasonable to surmise that, absent PEDs, that equilibrium might have persisted over the past 20 years? Questions to ponder.