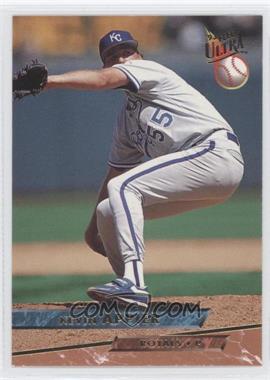

This 1993 Fleer Ultra card perfectly captures Kevin Appier’s deceptive (and unique) delivery. He would use that delivery to earn over nine wins above replacement in 1993. (Image courtesy of comc.com)

As I built the Hall of Stats, I came across many players who are rated highly by Hall Rating (a formula based on Baseball-Reference‘s WAR and WAA) but not remembered in the same way by Hall of Fame voters and the general public. I have covered several of those players here—including Larry Walker, Rick Reuschel, Curt Schilling, David Cone, and Urban Shocker.

Many players of this ilk are considered Hall-worthy by objective-minded fans—even if the Hall of Fame voters don’t necessarily agree. I recently named my Personal Hall of Fame while bloggers Bryan O’Connor, Ross Carey, Dan McCloskey, and Dalton Mack did the same.

I’m interested in consensus—particularly where these Personal Halls of Fame, the Hall of Stats, and Baseball Think Factory’s Hall of Merit agree about a player and the Hall of Fame does not. Just looking at the players above, so far Walker, Reuschel, and Cone are supported by everyone except the “real” Hall of Fame. Schilling is missing only induction from the Hall of Merit while Shocker isn’t supported by either the Hall of Merit or Bryan’s Hall).

Today, I want to talk about the player who ranks #1 in Hall Rating among players left off every one of these lists—that is, until Dalton included him. It’s Kevin Appier.

Appier, a right-handed starting pitcher, made his debut for Kansas City in 1989. He pitched for the Royals until a trade in 1999. From 1999 until 2004, he bounced around from the Athletics to the Mets to the Angels before finally returning to Kansas City. He won 167 games and lost 137 (playing mostly for a miserable Royals team). He posted an ERA of 3.74 (during the height of the steroid era, which helped push his ERA+ to 121).

What caused me to look closer at Appier was a comment at the Hall of Stats by Eric Ho Rulz. “Eric”, who I assume is a Royals fan who saw Appier often, questioned my easy admittance of Bret Saberhagen into my Personal Hall while Appier received barely a look. And it’s true—I wrote several articles where I debated the players on my borderline. Appier was even left out of those.

But it turns out Saberhagen and Appier have pretty similar value numbers. They both have around 2,500 innings, making comparisons even more convenient. Saberhagen had a 121 Hall Rating, powered by 59.1 WAR and 36.9 WAA. His top three seasons by WAR were 9.7, 8.0, and 7.3. Saberhagen’s most similar pitcher is actually Appier (with a similarity score of 129).

Appier had a 112 Hall Rating, powered by 55 WAR and 30.7 WAA. His top three seasons (this surprised me) were worth 9.3, 8.1, and 6.1 WAR. Saberhagen is listed as Appier’s fifth most comparable pitcher, trailing CC Sabathia, Mark Buehrle, Dave Stieb, and Jimmy Key.

Now, the premise of this comparison is moot if you don’t consider Saberhagen or Dave Stieb to be Hall of Fame-level pitchers. But Stieb actually gets a solid amount of Hall support in sabermetric communities (as the anti-Jack Morris, or the 1980s hurler with the most WAR). In fact, Stieb and Saberhagen are both included in every Hall except the “real” one. Stieb has a 115 Hall Rating, powered by 57.2 WAR and 31.3 WAA.

Upon Appier’s appearance on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2009, Rany Jazayerli wrote an excellent retrospective of Kevin Appier’s career. It is through Eric’s comment that I decided to investigate Appier further. But it’s Rany’s column that really drew my close attention.

The article essentially reads as a laundry list of the ways Appier was overlooked over the years (and screwed by his teams). I’m going to go ahead and excerpt large chunks of it. I hope Rany doesn’t mind. You really should read the whole thing, though.

About Appier’s rookie season in 1990:

For the season he was 12-8 with a 2.76 ERA in 186 innings. If that ERA doesn’t impress you, it should: it remains the lowest ERA by an AL rookie who qualified for the ERA title since 1976, when The Bird was The Word: Mark Fidrych led the league with a 2.34 ERA.

Do you remember it being that notable? I sure don’t. And you don’t even need advanced metrics here. We’re talking ERA. Rany continues:

For his efforts, Appier finished a distant third in Rookie of the Year voting, behind Sandy Alomar and Kevin Maas. Alomar hit a modest .290/.326/.418, but so bewitched reporters with his intangibles that he won the Rookie of the Year award unanimously.

Alomar was worth 2.3 WAR (according to Baseball-Reference). Maas was worth 1.2. Meanwhile, Appier was worth 5.3.

Fast-forward to 1992:

Liftoff came in 1992, when Appier had a 2.46 ERA, missing the league ERA title by just five points (Roger Clemens led with a 2.41 mark). Appier also finished third in the league in hits per nine innings, fourth in WHIP, fifth in homers per nine, seventh in strikeouts per nine…and thanks to a typically anemic Royals offense, 16th in wins with just 15. … He didn’t receive a single Cy Young vote. Dennis Eckersley won the Cy Young (and the MVP!) in a sort of delayed reaction to Eck’s 0.61 ERA the year before.

Ladies and gentelmen, that is an 8.1 WAR season from a pitcher who did not even receive a single vote for the Cy Young. I don’t just mean a first place vote—I mean no votes at all. Eckersley won it with his 2.9 WAR. Roger Clemens (8.8 WAR) and Mike Mussina (8.2 WAR) were legitimate candidates and finished third and fourth, respectively. Jack McDowell, solid with 5.3 WAR, finished ahead of all of them. He won twenty games. Clemens and Mussina won only 18. It’s frightening to remember how much wins dictated everything back then.

I remember feeling that Appier’s 1993 season came out of nowhere. Had I known a bit about advanced metrics at the time (I was only fifteen and my favorite baseball thing at the time was the bearded Phillies), I would have seen it coming. But man, what a year it was. Like, a 9.2 WAR year.

In 1993, there was no debate: Kevin Appier was the best pitcher in the American League. He led the circuit with a 2.56 ERA, a figure made more impressive by the fact that 1993 proved to be the first year of the juiced ball/bat/body era … Appier led the league in ERA by 38 points over Wilson Alvarez … But in 1993, Appier received exactly one first-place vote. He finished third in the voting, behind Jack McDowell and Randy Johnson.

Johnson won 19 games and fanned over 300, so you can understand the appeal. McDowell again won twenty (but this time with only 4.3 WAR). Rany points out how the win “difference” wasn’t really a difference:

Mind you, when McDowell started, his team went 23-11, and when Appier started, the Royals also went 23-11. But because of the way baseball’s arcane, century-old scoring rules work, McDowell was credited with four more wins. A trick of accounting seemingly concocted by the wizards at Arthur Andersen gave 28 sportswriters the perception that Jack McDowell was the better pitcher, and gave Appier the shaft. Appier was already used to getting the shaft from his teammates, so it was only fair that their inability to support him offensively would screw him one more time.

Just think for a minute about the affect this had on how we remember Kevin Appier. If Kevin Appier had played with Jack McDowell’s offense behind him, we’re looking at a guy 25 years old with a first place Cy Young finish, a second place Cy Young finish, and a Rookie of the Year-worthy campaign to boot. Instead, Kevin Appier is barely remembered. I devour everything I can about players overlooked for the Hall of Fame. Nobody talks about Appier for the Hall of Fame. But that’s because nobody talked about him for Cy Young Awards when he deserved them.

It’s basically double jeopardy.

On his Baseball-Reference page, the strike-shortened 1994 looks like a down year for Appier. But Rany provides some perspective there:

In 1994, Appier’s ERA rose to 3.83, but then the league ERA rose to 4.81, and his ERA+ was still an outstanding 130. Teammate David Cone got the run support that Appier had been asking for, went 16-5 and won the Cy Young Award.

In 1995, manager Bob Boone used Appier in a very effective four-man rotation. Check out how he started the season:

Appier didn’t respond to this workload by pitching well. He responded by pitching brilliantly. His brilliance was evident on Opening Day, when he threw 6.2 no-hit innings before he was pulled from the game, as the strike which had come to a sudden end at the hands of future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor had necessitated a shortened spring training, and pitchers’ arms were not fully stretched out by the start of the season.

So, the strike caused Appier to leave a no-hitter in the seventh because his arm wasn’t stretched out yet. It’s a weird story, but so typically Appier at this point. Just when you think he’ll get recognized, something like this happens.

Appier started the year 11-2 with a 2.04 ERA and was an All Star—if you can believe this—for the first and only time. But the pitch counts were rising and he finally went to the DL for the first time in his career.

I don’t remembrer this well, but Rany makes it sound like Appier’s injury marked the end of the four-man rotation forever—though it was really probably the high pitch counts in games rather than the more frequent work that was to blame.

Boone’s experiment was actually a qualified success – Mark Gubicza, who hadn’t thrown 140 innings since he tore his rotator cuff in 1990, stayed in the rotation all year in 1995, led the league with 33 starts, and had a 3.75 ERA. But the point that baseball people took away from the Royals’ experiment is that Appier broke down, and the fact that he was throwing a ridiculous number of pitches was lost in the shuffle. No team has made a serious attempt at the four-man rotation since.

He had some legendarily horrible run support at times with the Royals:

[I]n 1997 he had a 3.40 ERA, good enough for 7th place. That season his run support went from bad to worse; the Royals scored two runs or fewer in 15 of his 34 starts, and Appier went 9-13 despite an ERA+ of 137. In the last 20 years, the only other pitcher to throw 200 innings with an ERA+ of more than 130, and finish with a record at least four games under .500, was Jim Abbott in 1992, when he famously went 7-15 despite a 2.77 ERA.

Appier injured his shoulder after that 1997 season—but not on the field:

Appier’s shoulder did come apart after the 1997 season, ending the opening act of his career, but the injury occurred in an off-field incident, reportedly when he slipped and fell of the porch while carrying some of his sister’s wedding presents. (Yeah, I know.)

He eventually came back but was traded to the Athletics at the deadline in 1999. Something weird happened in Oakland in 2000—Appier pitched with some run support. He posted just a 4.52 ERA (104 ERA+), but was 15-11 for his efforts. In fact, after that 1997 season, you might actually call Appier lucky in the win column. Despite an ERA+ of an even 100, he had a .524 winning percentage in 158 starts.

In terms of Hall-worthiness, Rany himself actually says:

I can not, in good faith, make a case that he deserves enshrinement in the Hall of Fame. But I hope that at least one of the several readers of this blog who have a Hall of Fame vote will check the box next to his name anyway.

Honestly, I think that actually sells Appier short the more I look at it. But Rany goes on to say that the “binary, up-or-down nature of Hall of Fame voting” forces a player like Appier off the ballot quickly. He wasn’t polarizing like a Jack Morris or a Barry Bonds. He just wasn’t … there. It’s too bad.

I also don’t think I’m ready to make the leap to include Appier in my Personal Hall of Fame. It’s also very hard to promote his case when Curt Schilling, Kevin Brown, Rick Reuschel, Luis Tiant, David Cone, and others are still on the outside. But I’m glad I finally gave him the consideration he deserved. It was wrong of me not to do so.

But yet, it was so Kevin Appier.