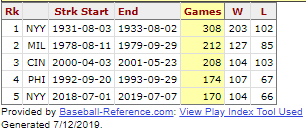

Home runs and strikeouts are both on the rise this year, to new record levels. So, what else is new, you say. Find out after the jump.

What’s new this year is the magnitude of the increases in whiffs and whallops, especially the latter. At the All-Star break this year, teams had connected for 3691 long balls, 408 more (11%) more than last year, despite having played 7% fewer games than in the first half a year ago. That total is also 379 more (10%) than in the previous record first half in 2017, despite playing only 1% more games in this year’s first half.

Looking at the number of players with 20 home runs by the All-Star break, there were 34 such players this season, 14 more than last year and 10 more than in 2017, and trailing only the 37 such players in 2000.

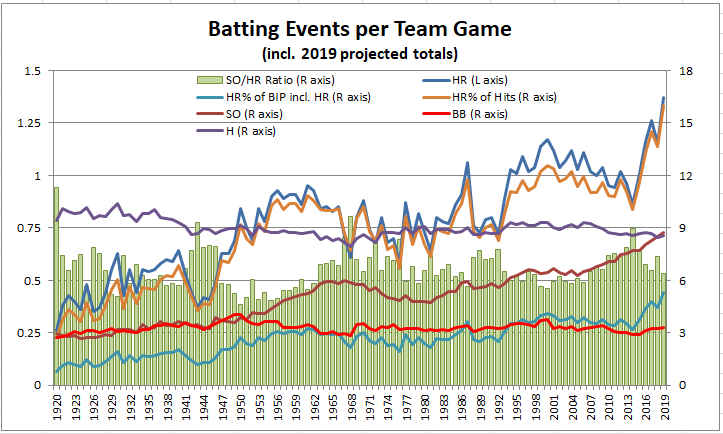

Projecting this year’s totals to a full season produces results that look like this.

Lots to talk about here, so let me explain. First, let’s look at what hasn’t changed much. That would he hits, which continue their very slow decline, but are generally averaging about 9 hits per team game for the past 75 years or so. And, walks, also basically steady at about 3 per team game. So, with essentially constant hits, the top two lines on the chart, HR per team game, and HR as a percentage of hits, pretty much track each other in lock step as you see on the chart. And, look at the increase since 2014, a mere 5 years ago – the home run rate has jumped from 0.86 per team game to 1.37 this year, a staggering 59% rise.

The other line showing a steady increase is strikeouts, crossing the hits line this year and last, as strikeouts have exceeded hits for the first time. That result combined with the rise in home runs has pushed balls in play ever lower, dropping below 25 per team game for the first time this year and last, after previous first time depths below 26 in 2015, and below 27 in 2009. Thus, compared to 2007, this year there are 11% fewer balls per game that fielders can make a play on. That trend is depicted in the turquoise line near the bottom of the chart, showing HR as a percentage of BIP plus HR, with a result of 5.3% this year compared to 3.2% in 2014, a 66% jump in just 5 years.

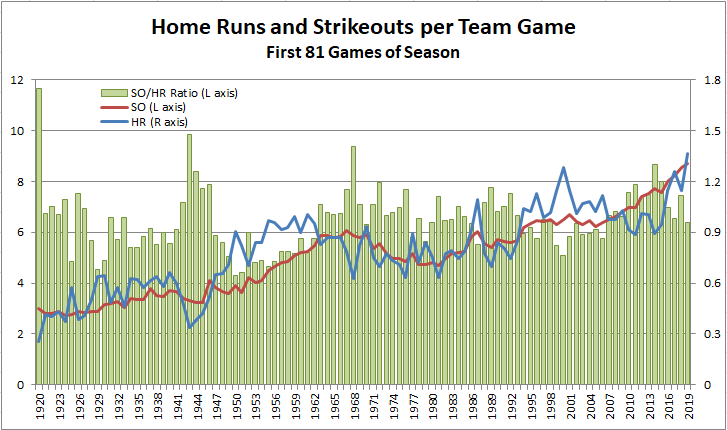

The last item on the chart is the ratio of SO to HR, showing a range between 6 and 9 for most of the past 60 seasons or so. That relationship may be more clearly appreciated in the next chart, showing home runs and strikeouts in the first half of the season.

Without the extra things on the chart, the fairly consistent relationship between home runs and strikeouts stands out more clearly. Mostly the two lines track each other closely, with home runs increasing faster than strikeouts only in the 1950s and the 1995-2005 decade, and strikeouts outpacing home runs only in brief periods, the longest being from about 2006 to 2014. In a sense, then, the big jump in home runs since 2014 has really been about “catching up” to the rise in strikeouts over that period.

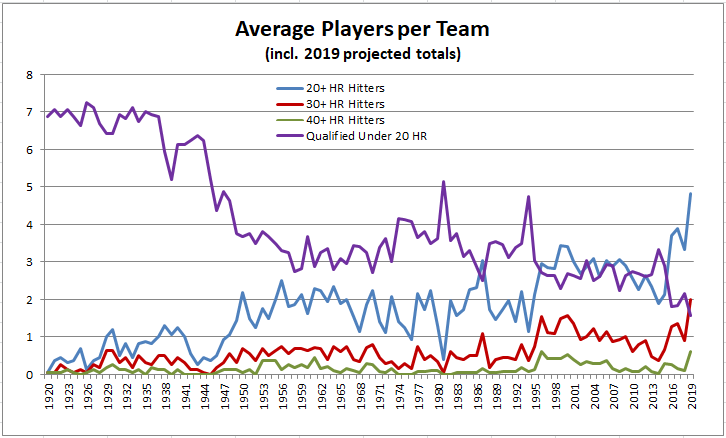

How do these changes manifest themselves at the team level. That result is shown in the charts below. First, for home runs:

The forecast for 2019 is for each team to average almost five players with 20 home runs, or 145 such players overall. That compares to 57 such players, or fewer than two per team, as recently as 2014. For 30 home run players, the forecast is just over two per team, more than the number of qualified players with fewer than 20 home runs. At the end of the 2017 season, games between the Cubs and Cardinals, and between the Cubs and Reds, featured as many as 11 players in a game then with 20 home runs; look for that record to fall this year.

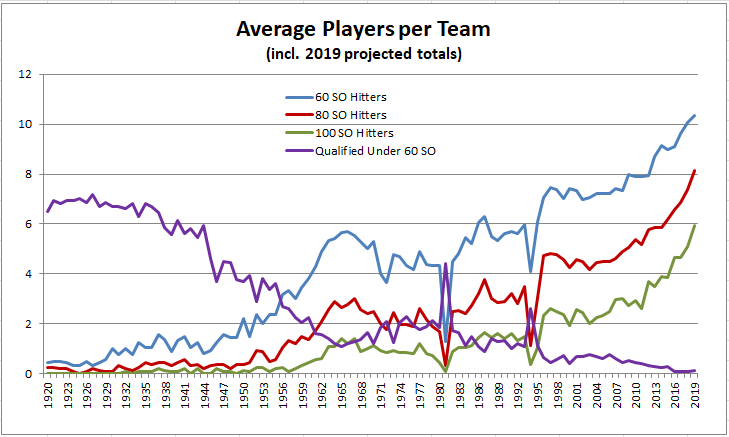

The picture for strikeouts looks like this.

Pretty much every regular player now will exceed 60 strikeouts, with an average of 6 players per team in triple digits, more than double the number in 2011.

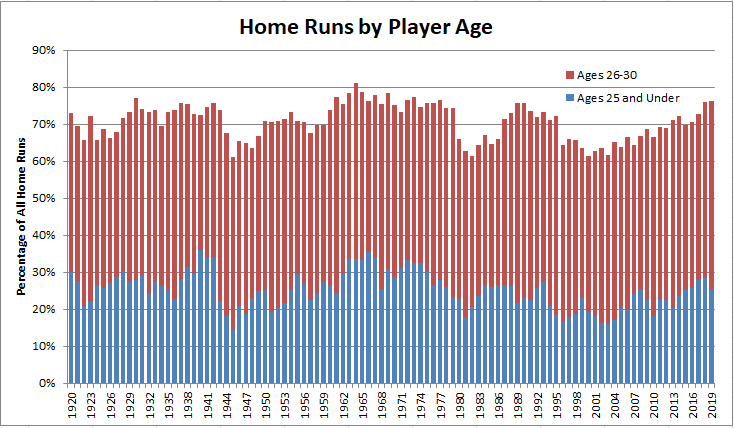

Who’s hitting all these home runs? That result is depicted below.

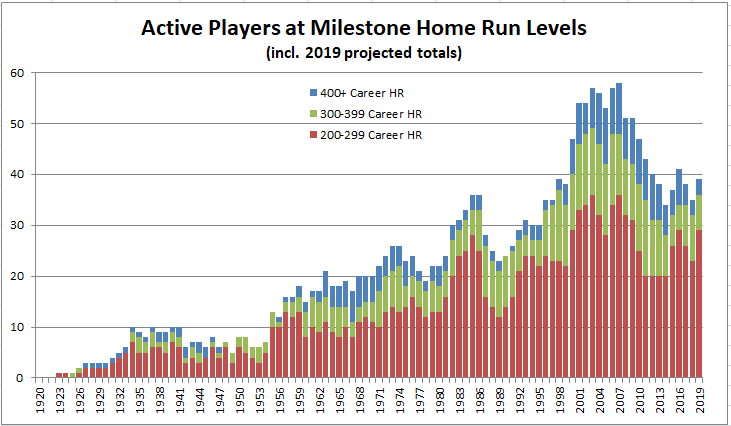

More than 75% of home runs this year will be hit by players aged 30 or younger, not a record proportion but in the same ballpark as the previous highs in the 1960s. It’s also a marked departure from the record lows just above 60% that were seen in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This change over the past 20 years has produced the result shown below.

With a larger proportion of home runs being hit by older players twenty years ago, the number of career 200 home run hitters peaked in 2007 before falling by more than a third by 2014. As the current large group of younger power hitters ages over the next 5 to 10 years, expect to see rises in the 200 home run club matching or exceeding previous record totals.