HHS contributor Michael Hoban has written a comprehensive paper on assessing career value for players of the past century (since 1920), commonly known as the live ball era. In Part 1. Michael introduced his CAWS metric, which stands for Career Assessment Win Shares, based on the Win Shares system developed by Bill James. In Part 2, Michael examines the relationship between CAWS and Hall of Fame-worthy careers.

In Part 1 of this series, I introduced the CAWS metric which takes the form of: CAWS = CV + .25(CWS – CV) where

CAWS = Career Assessment Win Shares

CV = Core Value = sum of win shares for a player’s ten best seasons

CWS = total career win shares

.25(CWS – CV) = longevity factor = credit earned for a longer career

Thus, to balance the quantity (length of career) and quality (core value performance) of a player’s career, CAWS credits players with 100% of the Win Shares for their best ten seasons, and 25% of their remaining Win Shares.

Hall of Fame Thresholds

In evaluating CAWS scores for prominent players of the past century, I’ve determined that the following thresholds provide the best correlation to career standards that are likely to be recognized by Hall of Fame enshrinement.

- CAWS score of 280 for right fielders, left fielders, first basemen and designated hitters

- 270 for center fielders and third basemen

- 260 for second basemen

- 250 for shortstops and catchers

- 220 for pitchers

The different benchmarks for each position recognize their positional scarcity which, for non-pitchers, derive from the different types and levels of defensive skills demanded of players at each position.

Based on these benchmarks, there have been 152 players (104 position players and 48 pitchers) since 1920 who have posted Hall of Fame numbers during their playing career. Ninety-nine (99) of these players have a CAWS score of 280 or better while fifty-three (53) others meet the adjusted HOF benchmark for their position, or one of the special HOF benchmarks for players with unusual or shorter careers (these will be explained below). The 152 players are distributed as follows:

- Pitcher – 48* (43 are in HOF)

- First base – 16** (10)

- Second base – 14*** (9)

- Third base – 10**** (7)

- Shortstop – 13***** (11)

- Left Field – 14 (10)

- Center Field – 11 (9)

- Right Field – 12 (12)

- Catcher – 12**** (10)

- Designated Hitter – 2 (2)

* incl. 1 active player

** incl. 2 active players

*** incl. 1 active player and 1 retired player not yet HOF eligible

**** incl. 1 retired player not yet HOF eligible

***** incl. 2 retired players not yet HOF eligible

A player is assigned (with very few exceptions) to the position where he played the most games during his career. So, for example, Paul Molitor and Frank Thomas are considered to be designated hitters because they played more games as a DH than at any one position.

One of the few exceptions to this rule, for example, is Ernie Banks. He played more games at first base (1259) than at shortstop (1125). But in everything I have read (and in the Hall of Fame), Banks is always referred to as a shortstop. So, I regard him as such.

The CAWS Career Gauge suggests that any player who has achieved the CAWS benchmark score for his position has Hall of Fame numbers. The question then arises: What about players who have not achieved these benchmarks, but who appear to have had a great, shorter career? I will address these exceptional cases next.

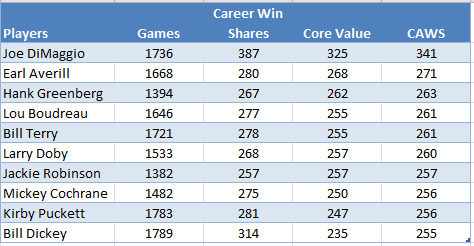

The 250/1800 Benchmark – Jackie Robinson

Jackie Robinson is a player whose contributions to the game went far beyond his considerable achievements on the field. As most fans know, Robinson had a rather short career of only ten seasons, chiefly attributable to the baseball color barrier that had existed prior to his career. While it is certainly true to say that a player who has such a short career usually will not be able to post Hall of Fame numbers, it may come as a surprise to some when I state that Jackie actually did post HOF numbers during his brief career.

Conversely, it will come as no surprise to most fans to learn that there are some players who are in the Hall of Fame but do not have Hall of Fame numbers, with examples like Chick Hafey and Rick Ferrell that come readily to mind. And there is another category of players, such as Dick Allen and Darrell Evans, who do have HOF numbers, but who have not been elected to the Hall for one reason or another.

Since 1920, I have found only ten position players who attained a CAWS score of 250 while playing in fewer than 1800 games. Every one of these ten has been elected to the Hall of Fame despite playing in relatively fewer games than their contemporaries.

Of course, Joe DiMaggio stands out among the players in this group as the one who achieved the most in a relatively short career. But note that Jackie Robinson played the fewest games among this elite group – and yet he was still able to achieve the CAWS benchmark.

Bear in mind that, while the above players met the 250/1800 benchmark for their careers, some elite players do so well before their careers end. Albert Pujols is a prime example: he is still active this year in his 19th season, but achieved the 250/1800 benchmark almost a decade ago, in 2010.

As an interesting aside, note how close the numbers place Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby – the two players credited with integrating the National League and the American League, respectively. Each of these players had a core value (CV) of 257 meaning that each averaged almost 26 win shares over his ten best seasons – an outstanding accomplishment. So, aside from being the integration pioneers, both Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby were terrific ballplayers.

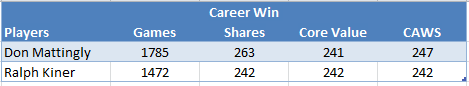

Keep in mind that there have been other outstanding players who have played in fewer than 1800 games in their careers – but who did NOT achieve the 250 CAWS benchmark. Here are two, one (Kiner) who is in the Hall of Fame, and one who is not (Mattingly).

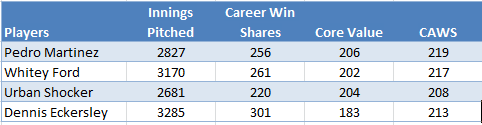

High Peak or High Career Value – Pedro and Eck

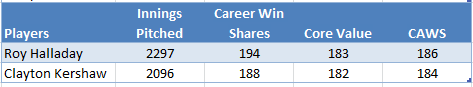

The HOF benchmark for pitchers is a CAWS career score of 220 that has been achieved by only 35 pitchers since 1920. The question then arises: What about a pitcher who has not achieved this benchmark, but who appears to have still had a great career?

A few pitchers who fall short of the 220 CAWS threshold nonetheless compiled stellar careers. A career with a high peak value is evidenced by a 200 Core Value (sum of ten best Win Shares seasons) that a couple of the 220 CAWS qualifiers did not achieve. And, one pitcher (with a notably unique career shape) recorded a high career value of more than 300 career Win Shares without reaching 220 CAWS or 200 CV.

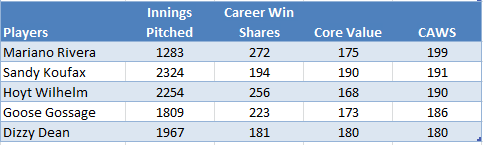

The 180/2400 Benchmark – Sandy and Dizzy

To fairly recognize exceptional performance by starting pitchers with shorter careers, or relief pitchers with very long careers, I’ve identified 180 CAWS in a career of less than 2400 IP as a suitable benchmark.

All five of these pitchers are in the Hall of Fame and deservedly so since this is quite an accomplishment. In fact, these are the ONLY PITCHERS since 1920 that I have found who have achieved a CAWS score of 180 with fewer than 2400 innings pitched.

But what if a pitcher had achieved this benchmark at some earlier point in his career? Logic would dictate that the pitcher in question had accumulated Hall of Fame numbers at that point in his career irrespective of what happened subsequently.

If you examine Pedro’s career through 2004 (his thirteenth season), he had already reached a CAWS score of 180 in fewer than 2400 IP, putting him in company with Koufax and Dean, whose careers were less than 13 seasons. Only two other pitchers since 1920 have reached the 180/2400 benchmark by their thirteenth season.

Therefore, in the live ball era, only eight pitchers achieved a CAWS score of 180 in fewer than 2400 innings – and the seven who are eligible are now in the Hall of Fame. So, for a pitcher, 180/2400 becomes a Hall of Fame benchmark.

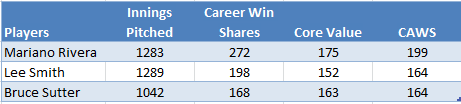

The 160/1500 Benchmark – Mariano Rivera

As we just saw, Mariano Rivera has HOF numbers because he is one of just eight pitchers who have earned a CAWS score of at least 180 in fewer than 2400 innings pitched. But Mariano is the extraordinary exception, a relief pitcher who meets the HOF standards for a starting pitcher. But, what should the HOF standard be for every other reliever who is not Mariano?

In wrestling with this question, I looked at the careers of all the great relief pitchers to try to establish a benchmark that would recognize the best – but would not be “too easy”. What I found was that only three pitchers since 1920 have achieved a CAWS score of 160 while pitching fewer than 1500 innings. Here are those pitchers, all of whom are in the Hall of Fame.

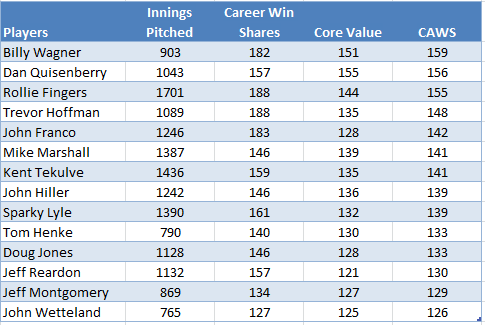

And, here are the CAWS scores for several other great relievers who did not reach 160 CAWS.

Only two of the relievers falling short of 160 CAWS are in the Hall of Fame, one (Fingers) who is recognized as being one of the pioneers of modern relief pitching, and the other (Hoffman) who is second only to Rivera in career saves, and more than 100 saves clear of Lee Smith in 3rd place.

In Part 3, I will present CAWS scores for all of the players meeting the Hall of Fame thresholds for their positions. If you don’t want to wait, you can look up the Win Shares for any player and, after cutting and pasting that result to a spreadsheet, you are a few clicks away from computing their CAWS score.