Lucky if you’re a batter, that is, and you’re facing the starting pitcher for the third time in a game. That scenario has always been advantageous for the batsman, but never so much as in the past two decades. After the jump, more on batting the third time through the order.

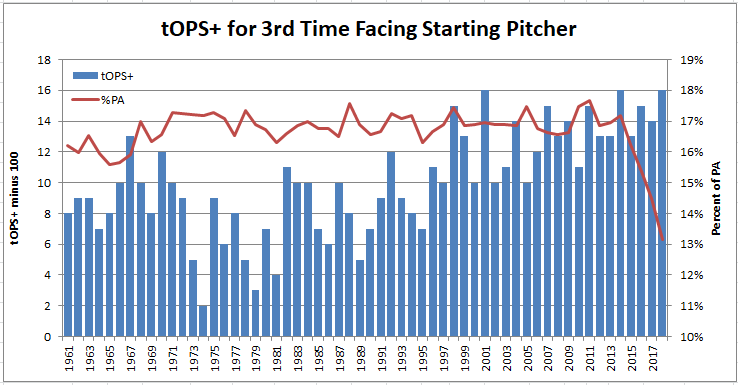

Focusing on the expansion era where game data are essentially complete, here is how batters have fared when facing the starting pitcher for the third time in a game.

By way of explanation, tOPS+ measures OPS+ in a “split” (in this case, for PAs facing a starter for the third time) compared to overall OPS+. In the chart, I’ve subtracted 100 from the actual tOPS+ to show the percentage improvement in OPS+ in this split. Thus, the result of 116 (or 16% better than overall OPS+) in 2018 matches the record high also achieved in 2000 and 2014, and marks the eighth straight year with a result of 113 or higher (compared to the previous record long streak of only three years).

The line in the chart shows the percentages of PAs represented by this split, which was consistently in the 16%-18% range every year from 1968 to 2013. Since then, that percentage has dropped sharply to only 13% in 2018, representing the ever diminishing workload by starters, which has dropped below 6 IP in the past few seasons. Curiously, though, the reduction in these PAs has not yielded better results for the pitcher, which might have been expected if for no other reason than selection bias (that is, the starters going the third time through the order would presumably be those pitchers who were pitching better on that day). The reason for the diminishing number of PAs facing a starter for the third time can perhaps be gleaned by the next chart.

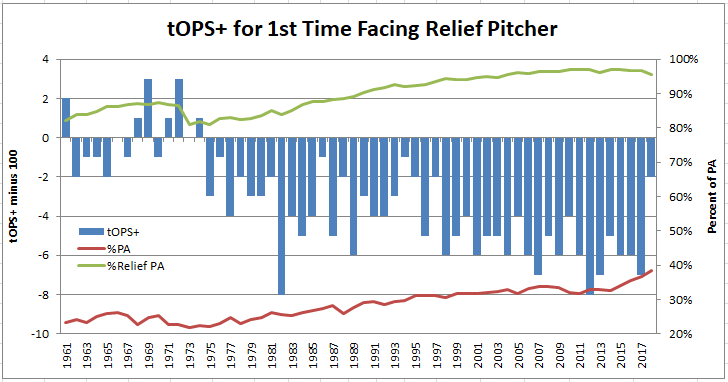

This chart shows the same tOPS+ data for the split represented by PAs facing a reliever for the first time (note that this is all instances of facing a reliever for the first time in a game, not just for the pitcher relieving the starting pitcher). Thus, batters have fared worse than average in this split every year since 1974, including a 7 year run (2011-17) with pitchers enjoying a at least a 5% OPS+ advantage (2018 saw only a 2% edge for pitchers, the lowest result since 1997). So, if a manager is debating whether to have his starter make that third trip through the order, evidence would certainly support going to the bullpen rather than rolling the dice on a tiring starter.

The lines on the chart also tell a story of the expansion and refinement of relief pitching. The red line shows percentage of total PAs represented by this split, which was below 25% before 1980 but now has risen to almost 40% of PA. The green line shows the percentage of relief PA represented by the split, which was in the 80%-90% range until about 1990, but is approaching 100% in recent seasons, with relievers now seldom asked to pitch more than two innings.

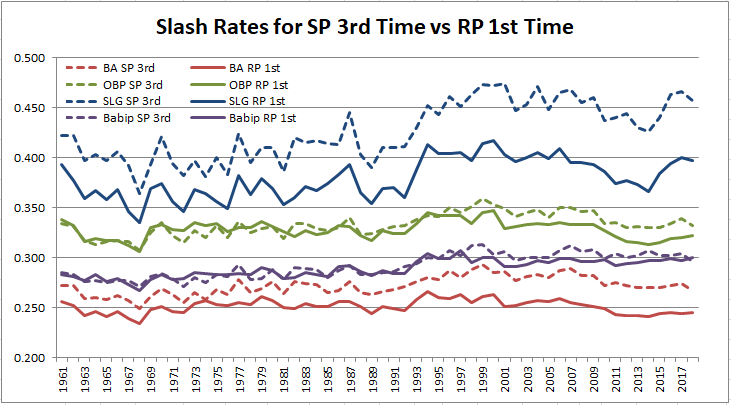

If OPS+ percentages above and below average are leaving you a bit nonplussed, here are those same results using more familiar measures.

A lot of lines here, so let me explain. The red lines are for batting average, green for OBP, blue for slugging and purple for BABip. And, all the solid lines are representing relievers facing a batter for the first time, while the broken lines are for starters facing a batter for the third time. Thus, when you look at the two lines for each color, you can see how much of an advantage or disadvantage the starter had compared to the reliever.

In batting average, relievers enjoyed a 10-20 point advantage in the early part of this period, and a 20-30 point advantage in more recent years. However, there was no OBP advantage to speak of for relievers until about 20 years ago, and it is still much smaller than the BA advantage. But, the biggest advantage, by far, is in slugging, going from a 20-30 point edge for relievers in the 1960s and 1970s, to a 50-70 point advantage in the past two decades. I added in the BABip lines because I was curious whether it would reflect the presumably harder contact indicated by those large slugging spreads. The harder contact is undoubtedly real, but it doesn’t show up in BABip (you’ll see why in the next chart).

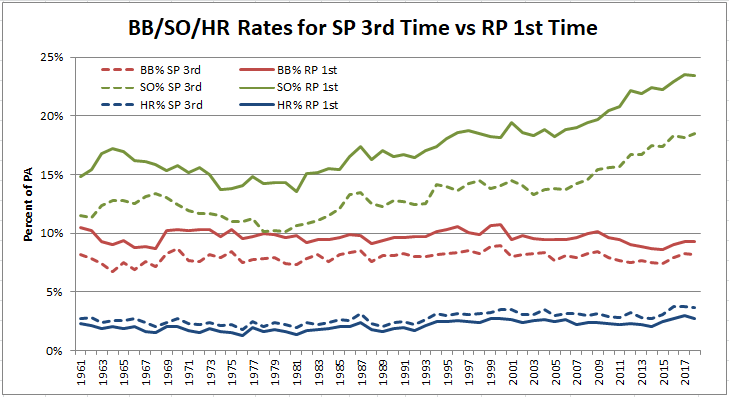

Same type of chart, except now showing the percent of PAs resulting in each of the three “true” outcomes of a home run, strikeout or walk. The one advantage enjoyed by starters facing an opponent for a third time compared to a reliever just entering the game is in control: the starter allows fewer walks, though that edge has narrowed in recent years to just a percentage point or two. Relievers, though, have the edge over starters in the other two metrics, a big one in strikeouts and a smaller but growing edge in home run rate. The one surprising thing (to me) about the strikeout edge is that it has been substantial throughout this entire period, not just in the recent past when almost every reliever seems to be a flame-throwing strikeout machine. And, don’t be fooled by the scale of the chart making the home run edge seem so small; relievers have had a 20% or better edge in home run rate vs starters in 11 of the past 13 seasons, including a 25% or better edge in five of those campaigns.

The big strikeout edge for relievers is the main reason that BABip results in the previous chart were about the same for starters and relievers. If you’ll permit me to exaggerate to make a point, let me suggest that when a reliever makes a mistake with a pitch, the batter will hit it hard, but when that reliever hits his spots, the batter doesn’t put the ball in play at all. If that batter were to cut down his swing to try to make more contact, or if that reliever were to occasionally ratchet down the fastball velocity a bit, just enough to put the batter off balance, then there would probably be considerably more weak contact against relievers, and a noticeable BABip edge for relievers compared to starters.