No, I’m not lamenting the unwritten rule that’s deprived us of left-throwing shortstops ever since Ragtime was the rage and hot dogs came with gloves — not right now, anyway. This is for the left-only batter, a species that’s become almost as rare.

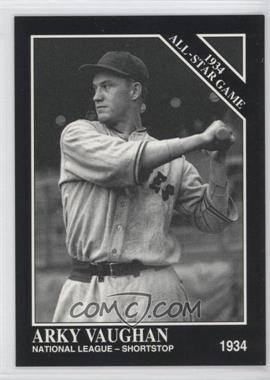

Left-swinging Arky Vaughan came to bat for the 5,000th time in 1939, and Cecil Travis followed in ’46. That made four LHBs out of 41 shortstops with 5,000 plate appearances to date. Now let’s play a game: Of the 78 shortstops to cross 5,000 PAs since then, think of one who hit left-handed only.

Got one? You’re sure? All right, then — I will now divine your answer:

It was Ozzie Guillen, who joined the club in 1995 — 49 years after Travis.

The 78 shortstops to cross 5,000 PAs since 1946 include 57 RHBs and 20 switch-hitters, but only Guillen from the left side alone. Just two other pure-LHB shortstops even reached 4,000 PAs since 1946, Tony Kubek and Craig Reynolds. That’s three 4,000-PA shortstops out of 94 total in the post-war era.

Of the others with 4,000 PAs in that span, pure lefty batters make up 16 of 98 second basemen, 13 of 91 third basemen and 18 of 74 catchers. That’s 18% for those other positions that “require” a righty thrower, but only 3% of shortstops.

In the last three years, shortstops logged 50 qualified seasons — 35 by righties, 14 by switch-hitters, and one by a lefty. Brandon Crawford, take your bow.

Now, there have always been fewer LHBs at shortstop than the other right-armed positions. But there’s still been a big change since WWII. Here’s the percentage of those with 5,000 PAs who hit left only, split in two periods:

- Through 1946 — 2B/3B/C combined, 20% (19/95) … 10% for SS (4/41)

- Since then — 2B/3B/C combined, 18% (32/181) … 1% for SS (1/78)

In the first period, shortstops with long careers had half the LHB rate of the other three positions. But while the other spots maintained their LHB rate, long-lasting LHB shortstops have virtually vanished.

Why So Few LHB Shortstops?

Is it a conspiracy? Is that why Stephen Drew still has no job? The only active LHB/SS within hailing distance of 5,000 PAs, he’s still two years away. The next two combined are less than halfway to 5,000 PAs.

Let’s try another tack. Here’s a breakdown by primary fielding position of all 182 “bats left, throws right” players with 5,000 PAs (with the traditionally right-throwing positions in bold):

- RF — 36

- CF — 31

- LF — 27

- 2B — 27

- 1B — 24

- 3B — 17

- C — 12

- SS — 8*

* Five of these eight meet the standard of “at least half their career games at SS,” used in the initial measures. Three others played more SS than any other spot — Sam Wise (48%), Johnny Pesky (47%) and Monte Ward (45%).

Shortstops comprised 8% of this BL/TR brigade through 1946 (6/73), but just 2% since then (2/109).

Some have theorized that the particular throwing requirements of the SS position make it best suited for those with strong right-hand dominance, making them less able to learn lefty batting.

But look at the positional breakdown of switch-hitting right-throwers with 5,000 PAs (103 players):

- SS — 27

- 2B — 24

- CF — 18

- 1B — 10

- C — 8

- 3B — 7

- LF — 5

- RF — 5

And if we deepen the pool to 182 switch-hitters (same as the LHBs):

- SS — 42

- 2B — 42

- CF — 27

- 3B — 22

- C — 15

- 1B — 12

- RF — 12

- LF — 10

Switch-hitters bat more often left than right, and shortstops lead the switch-hit parade. Does that fit the dominant right hand theory? Or does a right-hander’s decision to switch-hit reflect more athletic versatility than batting left-only? Among long-career players, shortstops are least likely to hit left-only, but most likely to switch-hit.

Which puts them in the middle of all right-throwers with 5,000 PAs who hit either left or both (285 players):

- 2B — 51

- CF — 49

- RF — 41

- SS — 34

- 1B — 34

- LF — 32

- 3B — 24

- C — 20

The real question, then, is why nearly all good shortstops who choose to hit left at all, choose to switch-hit — and why that choice is more prevalent at short than at second, third or catcher.

For Further Study

A deeper study of these trends would look at success rates and types of hitters among left-, right- and switch-hitters. The predominance of switch-hitting shortstops over LHBs could stem from slap hitters choosing to forgo their natural strength (such as it is) when doing so gives both a platoon edge and more chance of infield hits, but not becoming good enough as lefties to justify going left-only. Or maybe shortstops are more right-hand-dominant, and those who switch-hit are more successful and last longer because they keep some ABs from their strong side. But we’ll have to leave those questions for another time.

Besides, a change just might be coming. Last season saw a record six LHBs among the 34 shortstops with 300 PAs, and 13 in all who batted left or both (tied for the most ever). Four of those LHBs — the veteran Drew, 3-year man Crawford, and the rookies Brad Miller and Didi Gregorius — show promise of someday bridging the 5,000-PA barrier. (No offense to you, Messrs. Quintanilla and Descalso, Kawasaki & Gordon; but I’ve seen you hit, and … well, “no offense” just about sums it up.) The last two World Series champs started a lefty-hitting shortstop, raising that all-time total to seven (three by Kubek).

So, what do you think? Why have there been so few pure-LHB shortstops, but so many switch-hitters?